By Al (a bird)

What with all the cold and darkness, not to menshun the freezing cold and well, lack of sunshine, Hippo is just not herself. She even quit working on our article about essential oils. I reminded her that we have an important job to do – that the animals back home are counting on us – I tried pecking her head which usually brings her around – she didn’t blink. I even gave her one whole wallowday! I’m at the end of my tail – don’t overthink that.

I guess I’d better get going on writing this article myself.

To recap what Hippo and I already discovered, essential oils are chemical compounds extracted from plants, usually by distillation. Each plant has a unique essence or characteristic fragrance.

For example, rose essential oil is said to be the essence of rose. By the way, it can take fifty to sixty roses to make one drop of the oil. That upset Hippo – and me too, considering that rose oil production is measured in the tons. We also found out that roses are water guzzlers, upsetting us even more because we had seen the dried-up watering holes on the savanna and we knew some of our friends were going thirsty. Don’t think that I’m advocating for the abolishment of roses because thay drink too much. I’m not. It’s a matter of magnitude. The rapidly-growing essential oils business has gotten completely out of wing.

Hippo got excited about what she had read in an economix book. I’m putting it in big letters because Hippo thought it was very important.

Everything is produced at the expense of forgoing something else.

To put this in plain language, it means that in order to produce all those roses, something’s gotta give. I don’t want to just pick on the roses. “It takes nearly eight million jasmine blossoms, hand-picked on the day the flowers open, to produce just over 2 pounds of superior essential oil. For tart-sweet lemon balm, one of the rarest essential oils, upward of 3 tons of fresh leaves and flowering tops are distilled to make 1 pound of essential oil.” https://www.storey.com/article/essential-oils-sustainability/

In 2020, demand for essential oils reached an estimated 47.08 kilotons. https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/essential-oils-market I have no idea what that even means, but Hippo figured it all out and said that the amount of plant material needed to fill the great need demand for essential oils was more than the weight of all the elephants on the savanna. What we’re giving up for that is habitat and resources for others – like birds! And on the other end – the waste end – essential oils lose their effectiveness over time and may become something quite different and unsafe for use. Many are highly flammable and considered hazardous waste. Thay should never be flushed down the toilet because thay can make the aquatic plants and animals sick. I can’t stop wondering why anyone would go to all the trubble and expense and use of precious habitat to make essential oils and then waste them. I am scratching my head.

Hippo and I first learned about frankincense – no relation to Frankenstein – as we were reading about the human holiday Christmas which is coming up. Two thousand years ago, according to human lore, three wise men gave gold, frankincense, and myrrh, the most precious gifts imaginable, to honor the birth of a baby named Jesus. Frankincense and myrrh, both tree resins, are said to have been worth their weight (or more) in gold.

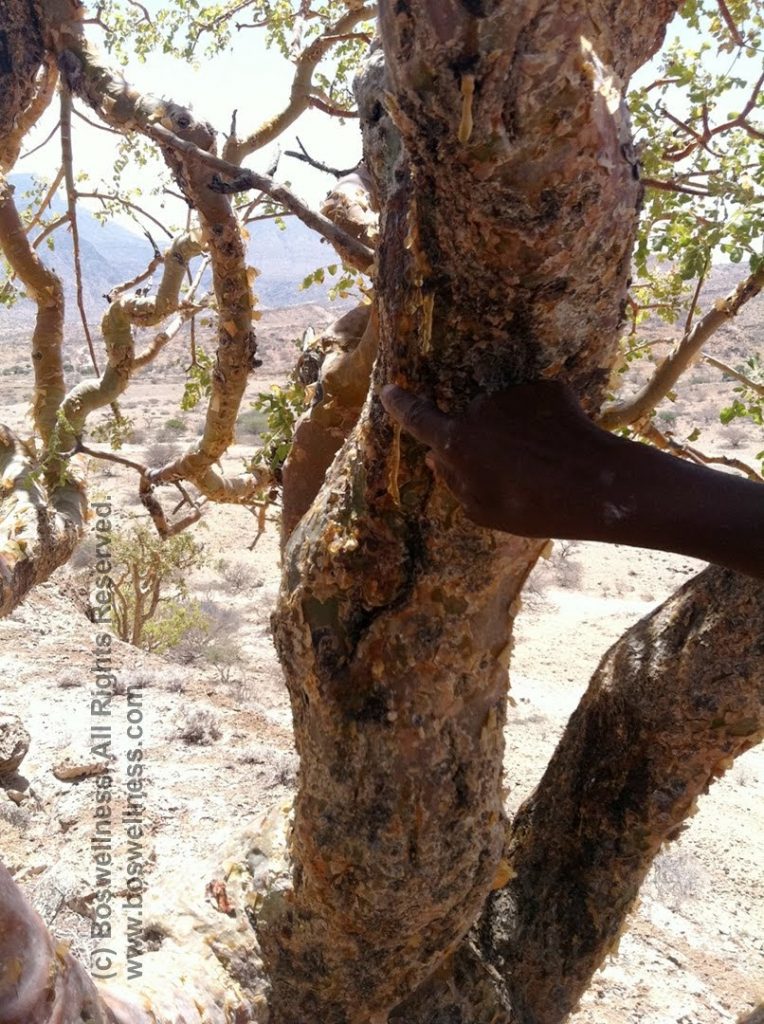

Frankincense comes from the sap of the Boswellia tree, native to parts of India, Africa and the the Arabian peninsula. For thousands of years, harvesters have been making cuts, or wounds, in the tree’s trunk to release the sap which is left to dry on the trunk and then collected. If the wounds are not too deep and not too often, the tree can continue giving for a long time. This is something like what they do here in Wisconsin with sugar maple trees to make syrup.

Frankincense was highly valued as incense, perfume, insect repellent, and salve for wounds. It was used to repair cracked pottery and as the heavy eyeliner worn by Egyptian men and women. Medical practitioners prescribed it for everything from arthritis to hemorrhoids. Today, it’s used as incense in sacred religious ceremonies and is one of the most popular essential oils.

When Hippo read that “frankincense is like liquid gold for your face” and Cleopatra’s beauty secret, she wanted to try it in the worst way. As you can imagine, Hippo has a hard time reaching many parts of her body so it is very difficult for her to keep her skin looking healthy without some help. I can only do so much. In the African rivers, she had the carp and other fish to clean her skin. Hippo was always beautifully radiant. But now, I could see that her skin was a bit lackluster and shabby-looking. She tried hard to appear indifferent, but I know it got her down.

Hippo faced a moral quandary. On the one hoof, she wanted frankincense to bring back her lovely skin, but on the other hoof, she knew of the environmental problems associated with the large-scale production of essential oils. Still she had hope that frankincense, from a tough and resilient wild tree with a long and celebrated history, might be different. Hippo was reading along quickly when suddenly she just stopped. I saw her deflate before my eyes – I hated to see that. She walked away without a word.

She had read some very disturbing information that amounts to this: Humans are over-harvesting frankincense – they are cutting too deep and too often – and the trees are dying.

If only she had hung in a bit longer, she would have learned that this is not necessarily true. There is much more to the story.

Böswellness

Böswellness (named after the tree) is a Vermont-based frankincense and myrrh distillery that sources its resins from Somaliland on the east coast of Africa. But they are so much more than that! Boswellness founder and native Somali, Mahdi Ismael Ibrahim, wanted to start a business that would lift up his native home, and that’s exactly what he, his wife and co-founder, Jamie Garvey, and business partner, Casey Lyon have been doing since 2005. Right from the start, they paid double the going rate for the frankincense and myrrh which made some people very angry. “We have this crazy idea that business can actually do so much good when it’s not solely focused on the bottom line. Not to say that profit isn’t important (or there would be no business), but reinvesting in the health and longevity of the local community is just as (if not more so) important.”

Boswellia and myrrh trees grow wild in the mountains of Somaliland along with animals and plants that are found nowhere else on Earth. Families have lived and worked among the sacred trees, foraging resin generation after generation. Because Founder Mahdi Ismael Ibrahim is Somali, and his family in Somaliland is also involved in the business, Boswellness has been able to work with and benefit the local harvesting communities, gaining their trust and respect in ways that non-Somali businesses can not.

Since we began the business, the price of the resin paid directly to harvesting families has increased 600%. The harvesting co-ops we work with set the price, and we pay it, without downward pressure tactics. When we first met with harvesters back in 2005 we learned they were receiving “payments” in the form of pasta, rice, or cooking oil, which were nowhere near equitable or fair. Cash payments at fair market value empower harvesting families to buy what they need. However, affordable access to food staples is a challenge due to the remoteness of the region. An example of how we met this challenge to improve quality of life is the food co-op we organized. We put up the money to buy the bulk staples the village needed at a reasonable price and transport them to the region. Then families purchase those staples at the same bulk price we paid, no markup. This increased buying power gets them more for their money. It’s not just increased wages that have improved quality of life. It’s also reinvesting into the community. They can’t be expected to use their wages to build out necessary infrastructure, like access to potable water, and unfortunately their government isn’t in a position to do it either.

That’s where business can step in and use their own resources (gained thanks to the producers) to build these things with the community. Our ongoing solar well project is an example of this.

But the most notable change is just how much the price has increased for resin in the past 15 years. It has also spurred a large number of new Somali-owned companies entering the frankincense trade. Whereas the job of a frankincense harvester was seen as a poor man’s job by my mother-in-law’s generation, today it is looked at as a lucrative business and one they can be proud of. This renewed interest and pride in the frankincense trade has also shifted from European controlled to Somali controlled.

Jamie Garvey, Co-Founder of Böswellness

“And what about the trees?” asked Hippo. I looked around. Where was Hippo? Then I realized that she was talking only in my head.

“Frankincense trees are beloved in Somaliland, Hippo. They are also vital to the survival of the communities. If the trees thrive, the communities thrive. And, it works the other way too. If the humans have enough food for their families, they can think of the future and of taking care of the trees. Böswellness is using a multi-faceted approach which respects this. Some day, I hope we can see the mountains and trees for ourselves – and the humans too.”

We recognize, as do the harvesters, that sustainability is very important to maintain these gifts which have provided livelihoods for centuries if not millenia and amazing benefits, both spiritual and medicinal, to so many people. Unfortunately, there has been a very effective misinformation campaign about Somali frankincense being overharvested. These unfounded claims have angered harvesters and brought deep distrust towards foreign researchers and self-proclaimed sustainability experts. The truth is, there are so many frankincense trees in Somaliland, the vast majority of them so remote, that there are still many that haven’t been tapped. The West has meddled in Africa for far too long with the goal of monopolizing resources and the current debate about frankincense sustainablity is no different.

Jamie Garvey, Co-Founder Böswellness

Böswellness is also involved with the Centre for Frankincense, Environmental and Social Studies, a Somali-based research center which is all about encouraging best practices among traditional foresters and harvesters.

Surprise

I am going to surprise Hippo with frankincense from Böswellness for Christmas. I can’t wait to see her face! She will be doubly pleased that humans are coming up with solutions where regeneration and human prosperity become possible. I can hardly keep my beak shut. Oh! I also found a book called Frankincense Resins, The Journey and Beyond by Robyn B. Kessler. Hippo will want to read this. There are recipes!

Boswellness sells most of its frankincense (and myrrh) to vendors, but they also sell directly to consumers through their website which is how I am buying it. They have resins, essential oils, as well as hydrosols. I’m getting Hippo the hydrosol – known by some as spirit water. When the frankincense is distilled, you get essential oil and hydrosol, the water portion of the distillate. It’s gentle on the skin and the Earth’s resources.

I have to think Hippo would be proud of me for writing this article by myself and I’m sure she would join me in recommending Boswellness. Here’s where you can get more information and order frankincense and myrrh:

www.boswellness.com

1 802-863-8005

Have you read The True Adventures of Hippo and Al yet? It’s an exciting tale filled with undercover disguises, menacing giants, and feats of great bravery . . . by me – the bravery part, that is. Read it here.