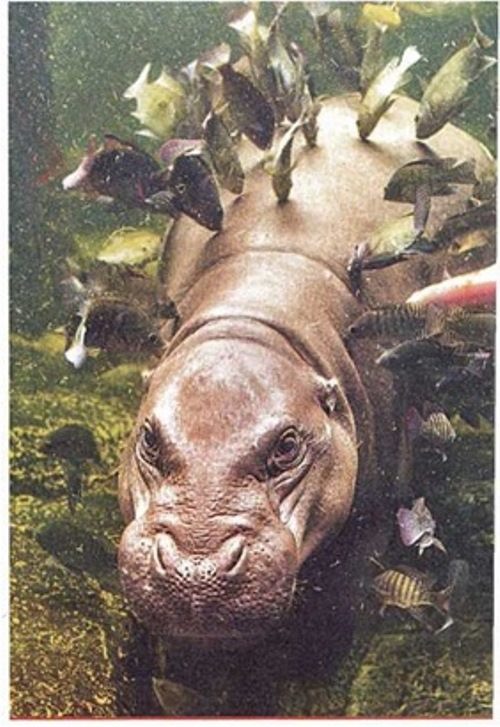

Hippo enjoys her river spa

“Maybe we can understand it better if we try to see it from the human point of view.” said Al.

“Excellent idea,” I cried. “I’ll pretend to be a human-thinking hippopotamus.”

“A group of us hippos gets together to clear out those deep, buried roots and bushes that get in the way of what we like best – tender, green shoots and creeping grass. We fence out the other animals, of course, even the other hippos, so they don’t eat up our food.”

“What about me?” asked Al.

“Of course, you can stay, Al. You don’t eat grass. And besides, I need you to eat the ticks off my delicate skin.”

I paused. “Oh Al, I said, “you’re my best friend. I couldn’t do any of this without you.”

“Anyway,” I added quickly so Al would not notice the wobble in my voice, “soon we’ll have a surplus of hippo grasses to feed more hippos. Our population will double.

“More hippos means more poop,” said Al.

“Never too much hippo poop, Al. Remember, it’s the lifeblood of the African rivers.”

“It could also become the death of the African rivers, said Al. “All those nutrients would feed an algal overgrowth, leading to oxygen depletion and death of fish and insects. Don’t you remember the dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico? . . . not from hippo poop, of course. It’s cattle poop and pig poop and even synthetic poop they use to fertilize crops.”

“Hmm,” I said. “I need the fish – the carp to keep my skin looking radiant, the brightly-colored cichlids to groom my tail hair. . . and the barbels to clean out the cracks in the soles of my feet. I guess we need to expand into more territory again.

“That would mean less water and resources for the others,” said Al. Their populations would decrease as yours increased.”

“But there is another option,” he continued. “We could take a few of the fish out of the river and build a hippo spa. You would have to pay them, of course.”

“Pay them!!”

“Well, they’re not going to clean your tail for free, Hippo. Without the river to live in, they’ll have expenses,” said Al.

“And there is another problem, Hippo,” said Al. “If you dig out all the roots and bushes that you don’t eat, your grasses will suffer, too. Those roots keep your soil from blowing away in the wind or washing down the river. They help it hold water for times of drought.”

“Hmmm. That’s what happened in The Grapes of Wrath,” I recalled. “American prairie farmers replaced millions of acres of diverse grasses and wildflowers with a single crop – wheat. When the drought came, as it often does on the grasslands, the crops failed. And without the massive roots systems to hold the soil in place, prairie winds scoured the earth, blowing millions of tons of topsoil across the arid lands.”

“But today we have irrigation,” said Al.

“Which often makes another problem,” I added glumly. “It explains why the animals’ watering holes are drying up.”

I felt overwhelmed. Maybe I had been too bold in thinking I could do anything to help. “Why did you get me into this, Al? What can one hippo do?” I wailed.

“If you’re going to start wallowing,” said Al, “you’d better get in the mud. “And don’t forget,” he added, turning slightly pink, “it’s not just one hippo. It’s one hippo and one bird. We’re in this together.”